Ukraine has a very long but complicated history — closely intertwined with Austria-Hungary, Cossacks, Poles, the Golden Horde, and more recently through occupation by nazi-germany, russia and the soviet union.

Once upon a time — the Kyivan Rus’

Ukraine’s history as inhabited land is ancient — spanning thousands of years. The borders of Ukraine have shifted over time a lot, not per se because the people themselves moved but because occupations and conquests brought people under different rules.

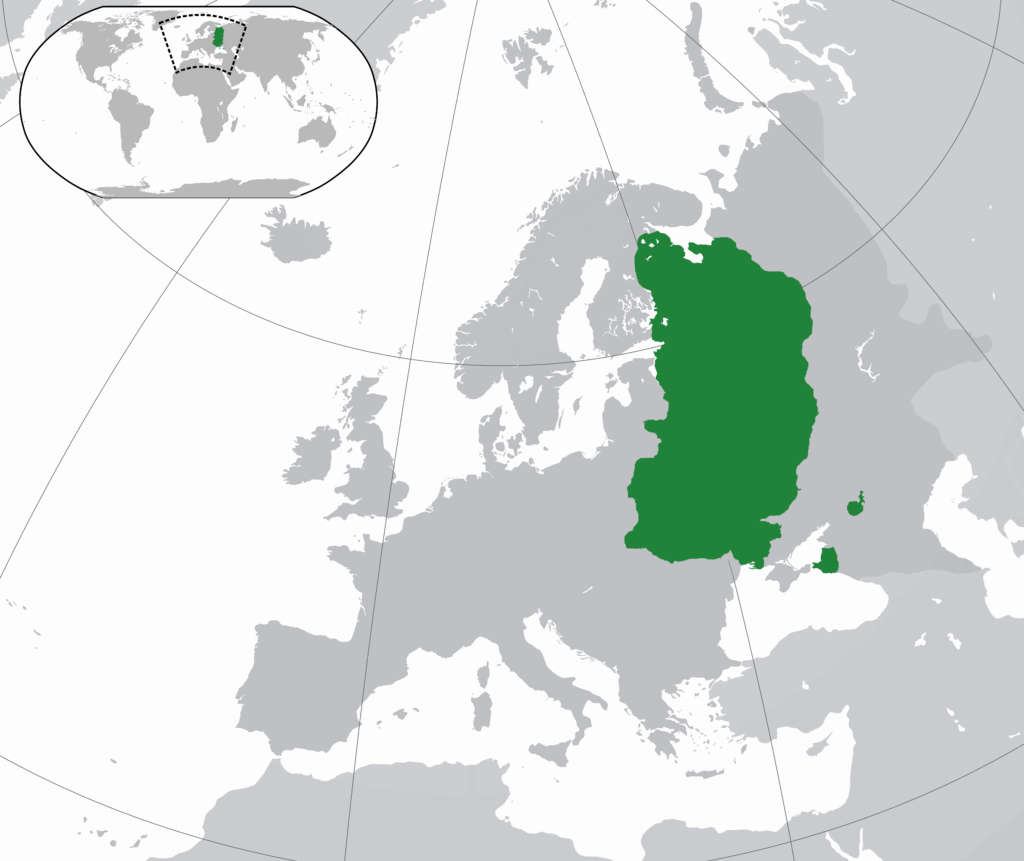

Originally, people on the Ukrainian land (and far beyond) called themselves the (Kyivan) Rus’. Per dominant scholarly view, the name Rus’ comes from Norse ‘Ruotsi’ (rowers or seafarers) — named after the viking traders from the north of Europe (the Varangians), who regularly moved to Black Sea ports in the South, and used Kyiv as their base.

The Kyivan Rus’ was a multi-ethnic state. Belarus and Russia also trace roots to the Kyivan Rus’. It declined after Yaroslav the Wise’s sons divided the realm, leading to fragmentation.

Seed of tension: the later russian state claimed the legacy of Rus’ through its name. It partially explains why russia can’t leave Ukraine to exist in peace. Kyiv is older than Moscow and even russia recognises Kyiv as “the mother city of Rus”.

In 988 — the baptism

Kyvian Rus’ was a pagan state, under constant threat of slavery and invasion. Being the borderlands between European civilisations to its West and nomadic steppe peoples, it needed to establish ties to fellow European nations and consolidate power for safety.

Religion was the primary means of that time to identify oneself as a people. Volodymyr the Great was baptised and christianity became the state religion of Kyivan Rus’, turning Kyiv in a religious and cultural centre. Being Christian next to other Christian nations promoted peace. And yet, with many different Christian denominations, a large Jewish population and a lot of paganism, the Kyivan Rus’ were quite tolerant of different religions.

Seed of tension: russia claims it inherited Kyivan Rus’ legacy. To justify the current war, russia even refers to this baptism in 988.

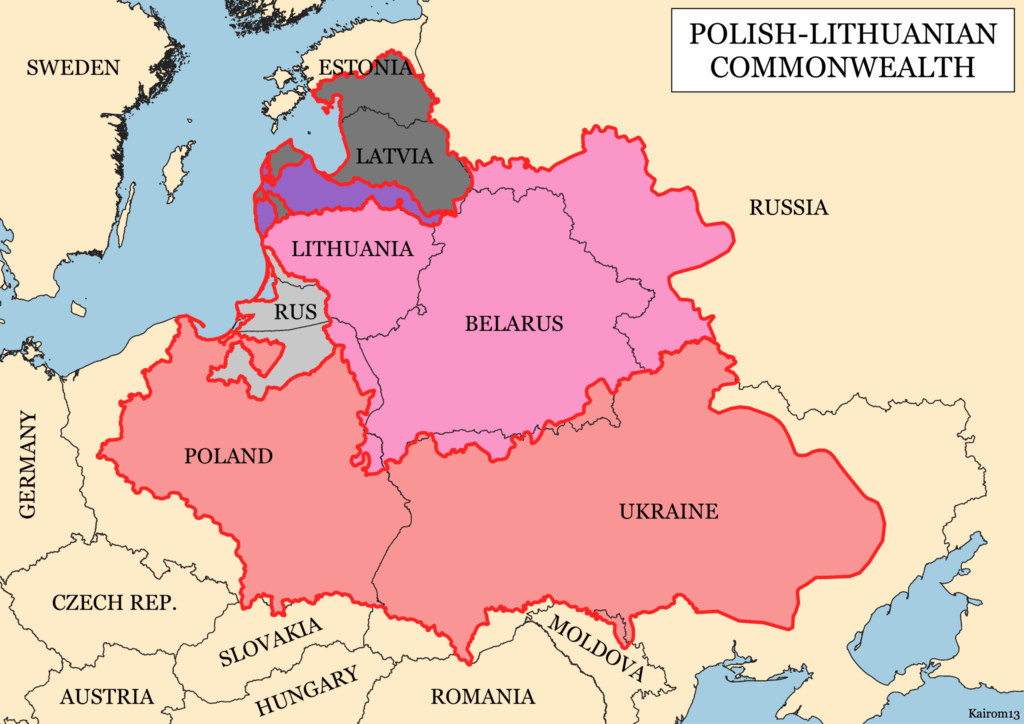

In 1648 — the uprising

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth rules much of Ukraine. The Poles are the dominant faction and their elites have settled in (mostly) Western Ukraine. Cossacks were free warriors, self-organised in democratic military councils — and played crucial roles in fighting for Ukraine’s autonomy and national dignity.

Cossack Bohdan Khmelnytsky leads a massive uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian rule. This lead to the creation of the semi-autonomous state ‘the Cossack Hetmanate’, and the birth of Ukrainian national consciousness.

Seed of tension: many wars followed, weakening the Hetmanate, causing it to eventually ally with Moscow (in 1654). The nature of this alliance is controversial — no actual treaty was preserved. The russians claim it was “voluntary reunification”; Ukrainians imagined “the alliance with a far away overlord” would leave them mostly autonomous. Instead, it seeded centuries of russian domination.

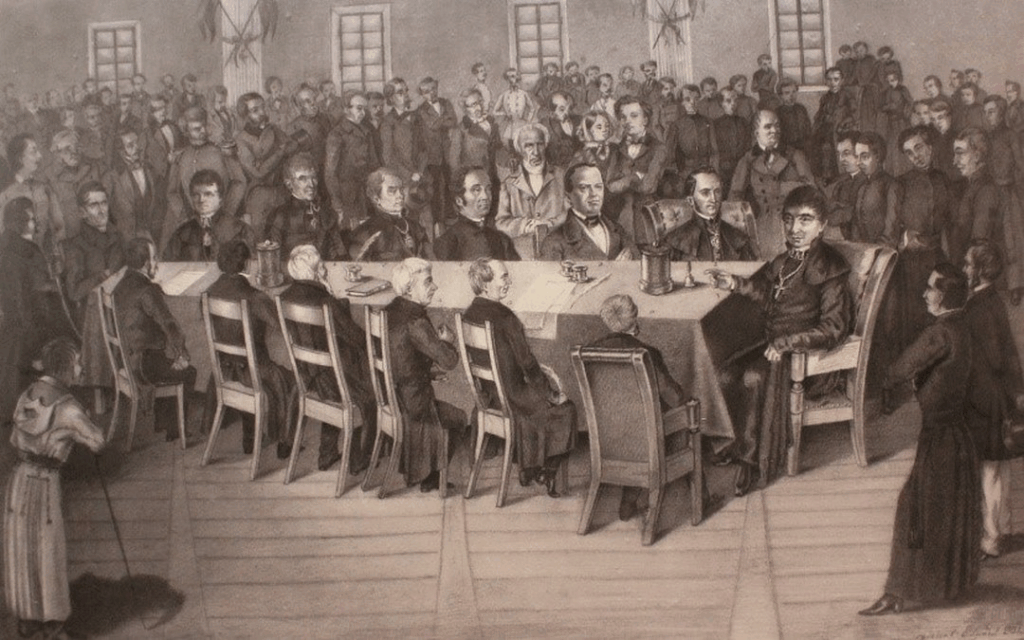

In 1848 — the Spring of Nations

At one time in European history, nation states were being born. This so-called “Spring of Nations” also reached Ukraine. Western Ukraine was part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire; Eastern Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire; the idea of a single Ukraine was still fragmented but forming. The name “Ruthenian” and “Ukrainian” were used interchangeably as well.

Some Ukrainian students from Austrian Galicia (in Lviv) form the Supreme Ruthenian Council. They discuss on what ‘Ukraine’ is or should be — and in doing so spark national revival and political demands for the Ukrainians. Initially, their demands were constrained to the Austrian part of Ukraine. However, this marked the beginning of the modern Ukrainian national movement.

Seeds of tension: the idea of Ukraine as a sovereign nation state caused a lot of border tensions and resistance within the two empires that dominated Ukraine at that time.

In recent years — the revolutions

In 1991, Ukraine became formally independent after the collapse of the Soviet Union. A long depression followed. Russia was accepted as the sole successor state to the Soviet Union, giving it major geopolitical and economic advantages. Also, as Myroslav Marynovych mentioned — no Nuremberg-like trials were organised for the many crimes during the soviet period, so no justice was served and impunity was the norm.

In 2004, Ukraines oppose massive electoral fraud, triggering the Orange Revolution and leading to new elections.

In 2013/2014, Yanukovych (who had returned to power) suddenly rejects the EU Association Agreement, and violently cracks down on protesters. The Revolution of Dignity follows — Yanukovych fled and a new government was formed. But Russia also annexed Crimea, began wars in the Donbas that are basically the prelude to the current days.

In conclusion

In 2022, russia launched the full-scale invasion on Ukraine. The Ukrainian’s don’t say the war started then — because it started either in 2014, or even much longer ago. One could argue the current war is caused by Ukraine’s centuries old wish for independence, and russia not letting them have it.

This war is not a ‘simple’ war but rather a reckoning with centuries of domination and oppression. It explains why Ukraine and russia are keen to fight this out to the end — losing this war would have enormous implications for either side.

If Ukraine loses, we will see russia permanently extinguish the Ukrainian identity where-ever it can. If Ukraine wins, russia’s impunity and domination may finally come to an end — and Ukraine’s independence may finally be complete.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to Yaroslav Hrytsak for two lectures on Ukrainian history and his proposed ‘three with eight’ years (988, 1648, 1848) that are critical to Ukrainian history.

Yaroslav Hrytsak is a Ukrainian historian and publicist. Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. Director of the Institute of Historical Research at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, visiting professor (1996–2009) at the Central European University in Budapest, and first Vice President (1999–2005) of the International Association for Ukrainian Studies.