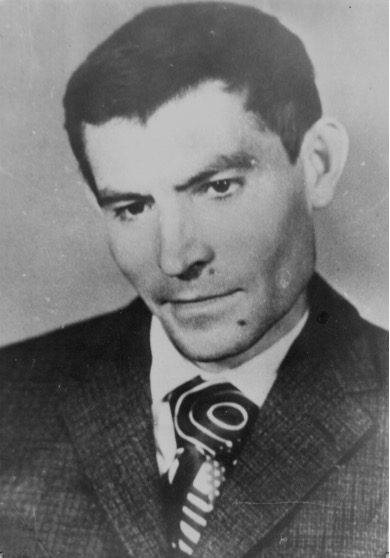

Myroslav Marynovych, a soviet-era dissident, gulag survivor and exile survivor, shared with us his story — along with reflections on how today’s war has roots in unpunished injustices of the past.

Today, Myroslav Marynovych is a Ukrainian intellectual, human rights defender, and advisor to the rector of the Ukrainian Catholic University — where the Ukrainian language course is given. Myroslav has also written a number of books, including the freely available “The Universe behind Barbed Wire“.

Myroslav Marynovych was invited and asked to share with us — language course students — his memoirs. While I hadn’t known about Mr. Marynovych beforehand, I’m truly grateful I got a chance to know him. His story was so inspiring, that we invited Myroslav back for a follow-up interview. In this post, I summarise his talk, the follow-up interview, and my own reflections.

(Note: a fellow language course student of mine published an article about Myroslav’s talk, relating it to the 4th of July. Do check it out! Another published the interview in Norwegian — very much worth the read as well.)

Becoming a dissident

Myroslav Marynovych is a well-known founding member of the ‘Ukrainian Helsinki Group’. Helsinki groups were formed in the soviet union (and Warsaw Pact countries) to document violations of ‘human rights’ in those countries, because upholding human rights was a condition for the Helsinki Accords (1975).

He draws inspiration from the ‘Sixtiers’ — an earlier group of Ukrainians who wanted to revive Ukrainian culture and advocated for “socialism with a human face“. They became dissidents when arrests began around 1965. Various waves of protests, suppression and activism occurred in the soviet union over the decades after. Membership of those Helsinki Groups also came in ‘waves’, because the soviet regime impressed, exiled, or otherwise punished nearly all of them.

There are many Sixtiers and Myroslav shared many names and photos with us — some lived to see freedom, others were murdered long ago. Myroslav endured both imprisonment in the gulag, and forced exile afterwards.

•The eternal shame of this country [the Soviet Union] will be that we were crucified on the cross, not for some radical civic position, but for our very desire to have a sense of self-respect, human and national dignity.

Ukrainian poet and dissident Vasyl Stus

The imprisonment

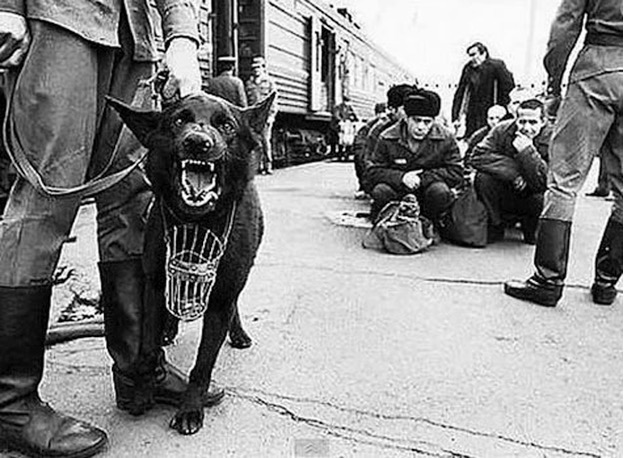

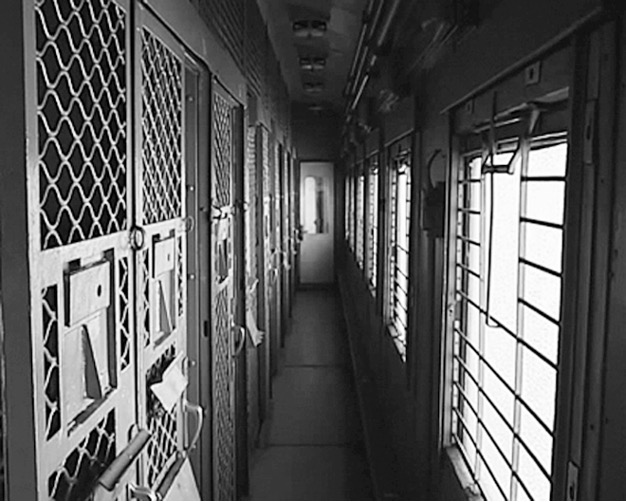

Myroslav Marynovych was warned by the KGB on 5 February 1977. It was followed by being fired, intimidation, secret apartment inspections, being labeled a (Canadian) spy and arrest on 23 April of that year for “dissemination of libellous statements with the aim of subverting the state authority”.

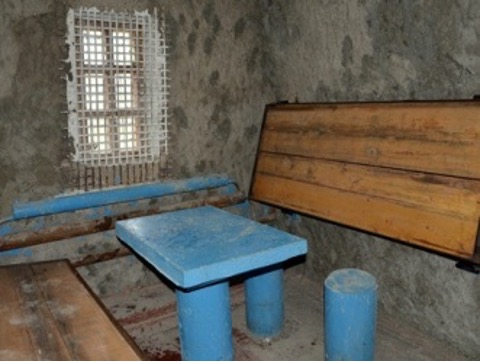

His trial was closed to the public and he defended himself, because no lawyer was trustworthy or brave enough to stand up to the state. He was sentenced to 7 years of labor camps, to be followed by 5 years of exile (in Kazakhstan).

In labor camp, the injustice continued. For singing a song, he was accused of “negatively influencing the negative experience of being a prisoner”. He was punished for praying on Easter. He went on a 20-day hunger strike for the right to read the Bible.

On justice: today we pay for past impunity

Members of Helsinki Groups were nominated for the 1978 Nobel Prize. The soviet regime even was ready to release members — because dictators are sensitive to pressure! However, at the time the political pressure from abroad was not strong enough, so actually nothing happened.

Marynovych argues that, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the West strongly recommended against launching another “Nuremberg” for the soviet union — even though the soviet regime was just as criminal and evil as the nazi regime. So, justice was never served — none of the regime’s prosecutors (KGB, police, courts) were held accountable. Some even advanced their careers after the soviet union’s fall (such as Putin from the KGB). Instead, people learned that one can commit atrocities and get away with it — directly setting the stage for Putin’s regime.

Realpolitik is wrong. It only plants the seeds for future conflict and crime. Justice is not about revenge by victims of the past — it is about preventing recurrence of crime in the future for everyone. Myroslav argues that Russia’s current war against Ukraine is the consequence of unresolved soviet crimes and global impunity.

On truth: today we pay for past lies

Even today, Ukraine is fighting an uphill battle to counter the propaganda and tentacles that russia has been successfully planting all over the world for decades — the US election interference, the Brexit referendum, other European politics affecting Ukraine, various countries in Africa. Myroslav said that that historical education in universities across the world often follows the russian version of history — in which Ukraine is just a footnote.

The insidious nature of propaganda is that one ultimately wants to believe it’s true. Producing bullshit is much easier than debunking it. And we also want to consume information that is easiest to believe — the simplest explanation, or rather: the explanation that doesn’t disturb our comfortable lifestyle, the explanation that doesn’t raise a dilemma or demand for action. And propaganda is tailored to be easy to consume.

Some countries in the Global South see Ukraine as a young nation, challenging an ancient empire. And, apparently, they do not see it as an anti-colonialist struggle. I suppose they believe the West is encroaching on russia, and Ukraine is just a tool from the West to ‘chip away’ at russia’s territory — making the West look like the ‘coloniser’ again.

In the Global South, many countries remember russia as an ally who fought against the colonialism by western empires. They can’t see russia as the bad guy — or perhaps think both sides are equally bad. The West may also lack the moral high ground to convince them otherwise — the West’s colonial crimes have not been judged by a Nuremberg trial of sorts either. In a way, our own impunity may thus also harm Ukraine.

On values: today we pay for past neglect

Myroslav calls on us to refuse lies and propaganda, to speak up in defence and solidarity with others, to act on conscience rather than convenience.

Myroslav gave an example about Crimea — he feels that Ukraine is honour-bound to liberate it and return it to the Crimean Tatars — the indigenous people that have been almost exterminated by the soviets and russians. The Crimean Tatars are fighting on Ukraine’s side to liberate the land and restore their autonomy and dignity. Myroslav states that peace plans that surrender Crimea to russia are immoral — it would force Ukraine to betray the Crimean Tatars and its own values. It is definitely an argument I have not heard before.

In the West, we (well, politicians) believed in “Wandel durch Handel” and they accepted making us dependent on russia with projects like Nordstream 1 and 2. The win-win-model is convenient because it doesn’t look for sacrifices. Our entire political system is tailored to tweaking, to negotiating, to compromising — not to making principled stances, or to rejecting temptations. But, as Myroslav says: win-win doesn’t work when the opponent plays win-lose (zero-sum).

In the West, we have (to some extent) lost the capability to set boundaries, recognise evil, and resist. Our world has rampant disinformation, superficial political discourse, transactional politics, and we can often ‘pay away’ our problems. There is little incentive to embrace, share and uphold values — and yet values are at the very core of justice, of dissent, of dignity, of what binds a society together.

I do not believe our Western society is evil, but I do believe we lacked courage and we neglected our values — and thus we allowed “never again” evil to rise “yet again”. The more people are driven by values, the less courage, risk and anxiety each individual needs to embrace to stay true to their values. Myroslav remarks that tyrants are also afraid — sometimes they are even more afraid than the good guys.

Those who are ready to give up essential values to obtain a temporary safety deserve neither values nor safety!

(Original by) Benjamin Franklin, (modified by) Myroslav Marynovich

In conclusion

The interview took place in the basement due to an air raid alert. We improvised sitting arrangements in the middle of the hallway — where one generally wouldn’t host an interview with such a guest. We were repeatedly interrupted by intercom announcements about the russian air raids. Interviewing a survivor of Russian crimes in these very circumstances is ironic, and in a way amplified his message.

We asked Myroslav what we should do after we leave Ukraine — and he gave us a simple answer: “Speak the truth, counter propaganda, share your experiences.” A seemingly simple task, but one that feels more profound after speaking with him and experiencing Ukraine first-hand.

During the presentation and interview Myroslav often smiled and spoke with a calm demeanour about very grave topics. I asked him: “After all that you’ve experienced, you still smile, you still seem happy — how is this possible?” His answer was “I have chosen my way, so I don’t complain.” He chose to become a dissident, chose his struggle and had only one goal — to not become angry, hateful or bitter. He achieves that goal to this very day with grace, an inspiration to us all.

So rather than complain, let’s choose our value-driven struggle — and stay happy regardless.

Wonderful article. A truly inspiring man and a treasure of Ukraine

Thank you, Wannu! Wonderfully written.