In the words of Yaroslav Hrytsak during his lecture: “Nations create war; war creates nations“. The Ukrainian people did not choose this war, but they did choose to respond with dignity. For those of us at peace, especially in the West, we must ponder: how do we retain our dignity?

The need for action

The Ukrainians pay dearly in this war — in time, money and blood. This is a war between decency and tyranny, between good and evil. It is far more than a ‘regional conflict’ — it is about the very value of human life, of personal freedom, of dignity. We share those values and we should share the burden of defending them.

Please help Ukraine as much as possible or as much as your dignity demands.

The dead

In the other blog post, I described our excursion to one cemetery. In this post, I want to discuss another cemetery: the Martian fields — where fallen military forces are buried.

Compared to last year, this cemetery has already doubled in number of graves — and this cemetery is just for those connected to Lviv, a relatively safe city.

Our guide highlighted one particular grave — that of Iryna, codename “Cheka”, a volunteer combat medic well-known across Ukraine. Her last message on Twitter was: “My birthday is coming soon, and I am proud to have lived to be 26.“

She was killed on rotation — just two days before that birthday. People across the country mourned her and she was declared a Hero of Ukraine posthumously. Every year on 1 June, her birthday, people organise ChekaFest in her honour.

Iryna is just one of the many good ones. Consider also Dmytro, who I mentioned in an earlier post. Looking around the graveyard, the amount of graves I see with birthdates later than 1990 or even 2000 is bizarre. A lot of young people are dying — for a worthy cause, but it is a price that should never have been theirs to pay.

Please also check out Lauren’s reflections on memorialising.

The amputee superhumans

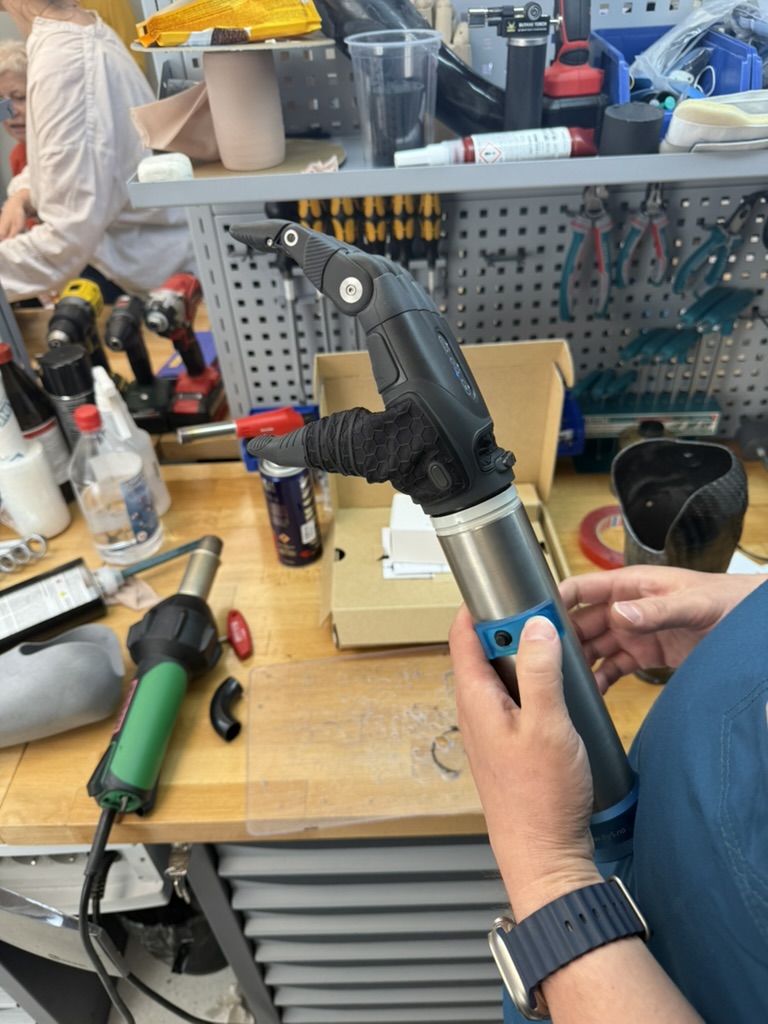

Almost every time I walk in the centre of Lviv, I see some men with missing limbs and prosthetics — undoubtedly caused by the war. There are rehabilitation centres nearby, such as the Superhumans center. We visited the center in Lviv to learn more. (Thanks to Lauren for organising this!)

Superhumans Lviv has rented hospital floors/sections from the local hospital. Getting the location up and running started in December 2022 and finished in April 2023. The location has 80 beds for 1200 patients; 600 patients on waiting list; with 20 to 30 new patients per week.

Superhuman’s mission is to give people their life back and make it even better. Their approach is unique — it integrates prosthetics and rehabilitation (while the government treats these as separate things). Superhumans treat loss of limbs, loss of vision and since recently loss of hearing and the related psychological trauma — for anyone who was harmed by the war: civilians, children and soldiers. Treatment is relative, because prosthetics simply aren’t always possible or even close to replacing the original — though innovation is happening rapidly.

The treatments are very expensive. A prosthetic costs 15.000$ to 100.000$. Superhumans spends 1 million dollars every month just on materials. Superhumans is a charity fully funded through grants and donations, including from the Dutch government (and you?). The Ukrainian government does not fund Superhumans, although they work together in other ways.

Superhumans doesn’t allow military uniforms on their terrain, to avoid traumatising their patients. However, the Superhumans brand is so strong that soldiers apparently dare to go to battle, knowing that Superhumans has their backs if they are ever dealt a bad hand. And after treatment, some soldiers even want to go back to the front.

Patients arrive in all sorts of states: 65% of patients have missing one lower limb; 20% one upper limb; 15% more than one limb. Many patients also experience survivorship guilt and think their life is over when maimed. Families of patients also tend to overcare, which is not helpful, because the very treatment is aimed at restoring personal autonomy.

The awesome dude in the earlier picture lost three limbs. In a revalidation centre in Germany, they said he wouldn’t walk again — they were wrong, clearly. Funnily enough, the dude got his decorated prosthetic first and decided to tattoo his arm stump to match. He even learned how to fix his prosthetic himself, because he broke it too often. How’s that for ‘restoring personal autonomy’?

Apparently Superhumans also have some very disturbing case(s) — some prisoners of war were caught by the russians with their limbs intact, and exchanged back to Ukraine with all four limbs missing. I’ve also read other stories of PoWs arriving back in Ukraine incontinent due to maiming while imprisoned. This gives you a sense of the sheer evil and cruelty we are up against.

The daily life

Not all impacts of war are as visible as graves or prosthetics. Day to day, the Ukrainians have to be resilient and navigate their lives around the war.

Ukrainians compartmentalise and try to continue life. However, they must often live by the day and don’t plan for the future much. They just “don’t look up” and do their daily duties with dedication and trust that if everyone does so, it will be enough. They’ll try to have fun and celebrate life despite the war — because they’ll simply go crazy otherwise.

And yet, Ukrainians also want to avoid normalising the war — so everyone donates part of their income to the war effort and tries to participate in rituals and events that prevent normalisation. I donate more than a couple of hundred euros every month and I still wonder if I’m doing enough — and I reckon Ukrainians themselves feel this tension even more intensely.

For young men, there is the extra threat of being drafted. It must surely be difficult to reconcile that your own government might claim your future in order to defend it in a national struggle for freedom and independence.

The war itself also causes a steady anxiety among the population, according to our guide. The church helps people to stay close to their humanity and not ‘become a dragon while fighting the dragon’. As russia attacks Ukrainian civilians almost every day, it causes immense hurt and hatred. But even if Ukraine isn’t bombing russian civilians in return, even the wish for russians to suffer the same taints one’s heart. And a corrupted Ukraine is a russian win as well. It requires effort to stay true to one’s principles.

Some Ukrainian families have members who currently live in russia, or were born there. And some of those members support russia in this war, and truly believe its Z-propaganda. I know some of those families stay in touch and instead choose to ‘not talk about the war’ — it must be agonising to arrive at that compromise.

The bittersweet

Ukrainians don’t allow this war to only inflict losses; the Ukrainians seize the moment and opportunities as well.

Paradoxically, in some ways the Ukrainian nation is stronger now than it has ever been. Ukrainians express their country feels more united and more oriented towards the ‘common good’ than before. Before, Ukraine was more individualistic or only family-oriented — many Ukrainians saw the ‘state’ as distant or to be avoided. That’s changing and I’m pretty sure this renewed civic spirit will do wonders in rebuilding, fighting corruption and becoming an EU-member.

Ukraine also has long been struggling with its soviet heritage and russian influences. The Ukrainian language was always under pressure, even after independence in 1991. While this war is about more than language, language can be a very powerful way to distance or distinguish oneself from the enemy. Since the full-scale invasion, many russian-speaking Ukrainians switched to Ukrainian or “Surzhyk” (a mix of russian and Ukrainian). They tend to do so gradually, first switching at home and to strangers, then switching languages to existing friends. One Ukrainian I know grew up speaking the Russian language, and recognises that cutting out russian is also cutting out part of himself. But he assessed that what remains afterwards better represents who he wants to be and how he wants to see himself — and so this loss is also an act of defiance and liberation.

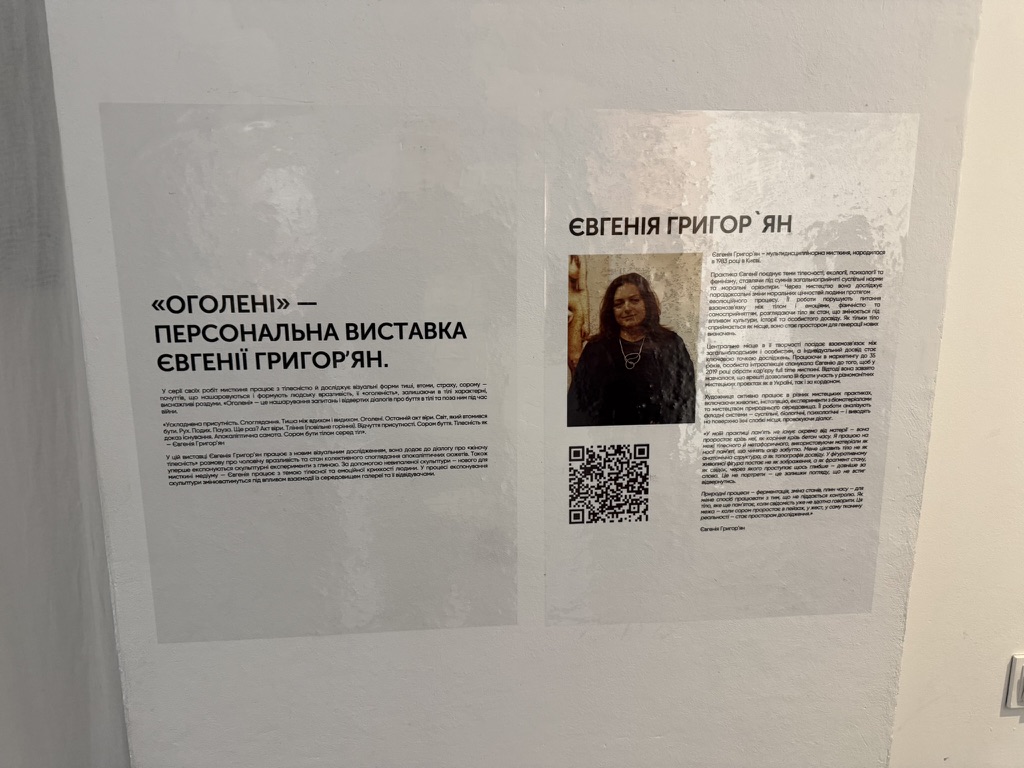

Culturally, Ukraine is also rapidly ‘liberalising’. I suppose this war for dignity makes people reflect on what ‘dignity’ actually means in context of outside pressures — be it a society at war or a society at peace. We’re not yet at LGBTQ-Pride-levels of personal freedom, but I’m pretty sure it’s on the roadmap. In many ways Lviv feels more modern and liberal than my Dutch hometown. In a small museum in the café where Raga performed recently, some works of Yevheniia Hryhoryan were on display. She didn’t paint men before but now she does — aiming to show their emotional vulnerability, challenging old norms on masculinity and nudity.

In conclusion

The Ukrainians have the strength to build their nation while at war, while suffering, while tired. They do everything in their power to survive, win and thrive — but they need help. And we, living in the peaceful West, owe it to ourselves to show the value of our principles and dignity by helping Ukraine defeat the aggressor as soon as possible.

Please help Ukraine as much as possible or as much as your dignity demands.