Monday’s placement tests would result in a division of students in groups on Tuesday. Groups had two or three students with similar skills and needs, one dedicated teacher and one dedicated practice tutor.

The schedule

The program for Tuesday and all future workdays is (in principle):

- 08:00 — 09:00 Breakfast

- 09:00 — 12:15 Ukrainian language lessons (including some breaks)

- 12:15 — 13:15 Lunch

- 13:15 — 14:00 Tutoring

- 14:00 — 14:45 Additional tutoring (if elected)

- 15:10 — 17:… Afternoon cultural activities (2 or 3 times per week)

The afternoon cultural activities include a city tour, a history class, music workshops and more. Apart from the workday program, some one-day trips are planned for some weekends.

The placement and first lessons

The twelve participants have been divided in groups of two or three people. Some participants have done this course in a previous year and will likely advance to a next level. Others are complete beginners. Still others have knowledge of Czech, Russian, or some other Slavic language — which is both a hindrance and a benefit.

In a way, this first week is one long ‘placement week’ — teachers assess what parts of the language people grasp easily and who require extensive repetition for what. So for now, we’re working with separate exercises and book fragments.

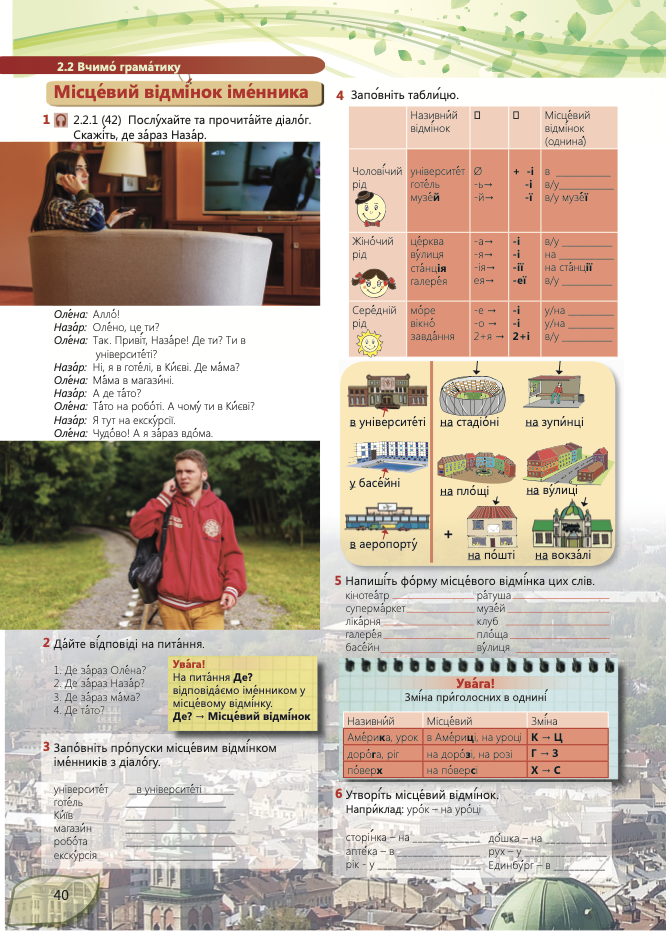

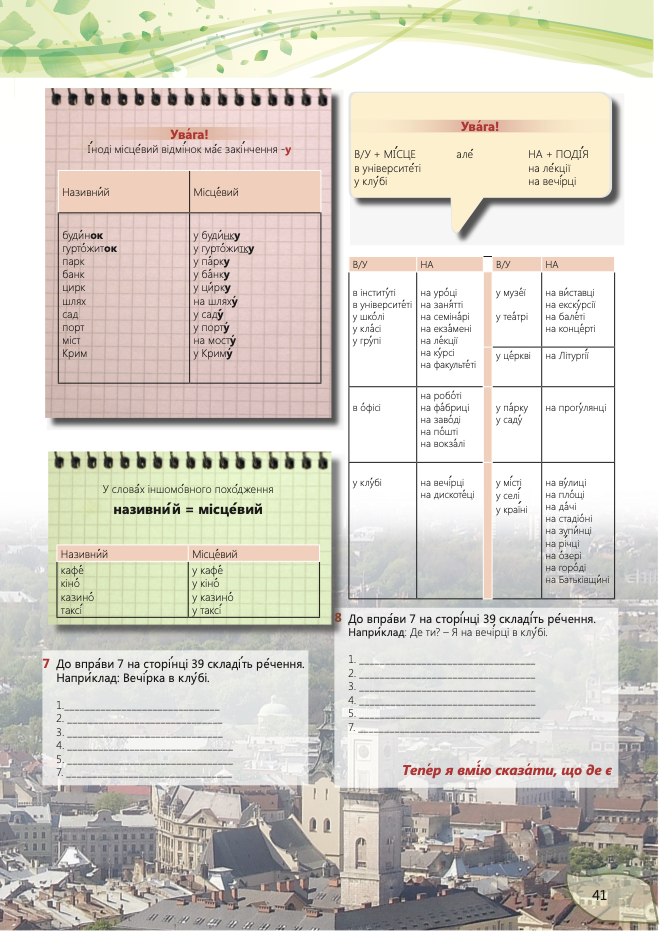

At the end of the first week, we’ll get our books — suitable for our level. The books (the Яблуко/Yabluko series) are made by the university and look really nice, so I’m looking forward to that. I’m sure nice pictures will make the homework fun! Right?

The materials and merch

Apart from actual class materials, we also got a notebook, a pen, a water bottle, coupons for breakfast and lunch, and a T-shirt and badge showing that we’re part of this training course.

I suppose the T-shirt and badge should be the equivalent of training wheels — a signal to native Ukrainians to have mercy to the foreigners. This mostly works as intended for the people ‘in the know’ (e.g., cafeteria staff). However, Wednesday morning I was having breakfast in the restaurant with (sitting opposite me) another participant of the language course — a retiree wearing an army cap. So that’s two men speaking English (one clearly American), both wearing army green shirts, neither of them well-shaved, and one of them wearing an actual army cap. Suddenly, a local university student popped by, thanked us for our service and walked away again.

I feel a bit dirty for not being in the army now.

The first language lessons

My group is a duo. My group mate knows Czech, German and (from long ago) some Russian. I suppose my half-memorised Duolingo/Memrise knowledge of Ukrainian gives a comparable advantage — we recognise many words ‘more or less’.

Our brilliant teacher and tutor have to be very tolerant with us, because we’re both very curious. “Why this and not that?” “But what about this?” “Can you give another example?” It’s like we’re trying to deconstruct the language faster than the teachers planned for. Satisfying our curiosity is not an option either because we’d just get overwhelmed.

We should shut up and listen more, but there’s just so many questions. The Cyrillic script is perhaps one of the easier parts. The counting system, the case system, the abundance of pronouns, prepositions, rules, the variations and exceptions to everything — it’s so bloody complex and intertwined. I am objectively mad for learning this language (just as anyone would be mad to learn Dutch).

In fact: my teacher, a polyglot knowing about 8 languages or so, touched German and vowed to never touch German or Dutch again — these languages have some admittedly crazy stuff going on with splitting verbs and jumbling word orders. However, and I’m writing it down here for posterity, evidence and for everyone to witness: my teacher promised to learn Dutch when I achieve C1 level of Ukrainian. (Perhaps she said “if” but I’m only hearing “when”.)

Time flies when you’re having fun — and our sessions are fun. There’s counting games involving dice, listening exercises, a lot of introductions to grammar, general rules, exceptions, exceptions to the exceptions etc. Our group’s relative polyglottedness comes in really handy — some language traits are really easy to explain by comparing to German rather than English, for example.

The first socio-cultural lessons

During our language classes there’s a lot of laughter and anecdotes. And equally important, there’s cultural lessons inside and outside these language classes. It’s interesting to hear reflections on Ukrainian culture from the mouth of Ukrainians.

We learn that Ukrainians are rather individualistic. They focus on their family, but not really on the country or society at large. However, this damn war, for all its horrors, changes that as it causes nation building in Ukraine. It’s not just Ukrainians coming together in this time of need to defeat the russians and survive, it’s also Ukrainians coming together to build a Ukrainian cohesion that just wasn’t there before and thrive.

We also learn Ukraine’s government is really digitally advanced. They have this app Дія (Diia) that allows citizens to basically do everything government-related in one app. I suppose the Wet op de Remmende Voorsprong applies to all those other countries (including the Netherlands) that were early with the digital transformation and now have difficulty modernising further.

There’s also an interesting relation with ‘privacy’. Ukrainians give out phone numbers easily, basically like people give out e-mail addresses. Ukrainians also tend to use one phone number for both business and private. In the Netherlands, phone numbers tend to be shielded a bit. Both in Ukraine and the Netherlands (at least younger generations) tend to hate sudden telephone calls, though — the phone number is to connect over Whatsapp (or Telegram), not for calling per se.

When exiting or entering Lviv, every car is photographed — with a noticeable flash. When I first experienced that, I thought people were speeding and not caring about the fine. My Ukrainian friend said — as a simple matter of fact — that the city tracks who’s in the city and who’s not “in case there are any problems”. As a Dutch person, this in-your-face government surveillance feels very intrusive — although I’m quite confident more surveillance happens in the Netherlands but hidden. It feels like the Ukrainian position is less hypocritical — the power dynamics are visible and you must resist, or you accept.

During the Lviv city tour (to be explained in another blog post), we also learned the Lvivians know their mayor is corrupt — gossip goes around. But he is less corrupt than the previous mayors, leaving enough for the city itself. And he knows that the people know he is ‘corrupt but less than others’. And the people know, that he knows, that the people know etc. It’s like the same social contract — there’s a balance of powers that everyone is aware of and they know that ‘you must resist, or you accept’.

In conclusion

The first few days of this course have already been more inspiring than I expected. The Ukrainian language and culture are very rich — and deeply layered.

I noticed many phenomena are not just explained by a long slow natural progression or evolution, but by relatively sudden events. For example: the many soviets attempts to rewrite history by covering the Ukrainian language and culture by thick oppressive layers. Correcting history and removing soviet layers isn’t so easy. Ukrainians can’t just pick up where they left off generations ago. Even if it were possible, it’d be a form of self-oppression to anchor Ukrainian culture to some past and thus prevent it from evolving in true freedom.

I’m witnessing in real time how a people reclaims its language and culture — and simultaneously claims a new future and freedom. I cannot help but see this struggle as a teaser of the one to come for the ‘ever closer (European) Union’, as we must also integrate disparate and conflicting histories into a European identity that works for everyone.

I’m not only learning the Ukrainian language functionally; for the free world, learning about Ukraine means to learn about ourselves.